Pliny the Elder, several editions (Lacus Curtius)

In August 1665, Lister read Pliny’s most famous work, which in turn would greatly influence his later work in entomology, conchology, and medicine. For a discussion from the BBC about the work’s larger significance, click here.

In the 1660s and 1670s, Lister began his assessment of works of natural history with Aristotle and Pliny because he was engaged in a comparative assessment of ancient and modern natural philosophers, a major preoccupation among intellectuals in the late seventeenth and first part of the eighteenth century. Lister acknowledged that Aristotle’s works on zoology, like his History of Animals had tremendous merit, as did Pliny’s Natural History, but knew that they also were often compendia of data not gathered from direct observation, but gleaned from written authorities. The encyclopedic means of gathering previous knowledge in natural history was changing with a new emphasis on direct observation.

In Pliny’s view, ‘historia’ included both the human and the natural sciences, so a medical case was ‘historia’, as was a history of past events, as was a history of animals and plants 1. And, throughout his career, Lister was also influenced by this tradition, his library having a heavy concentration of classical authors, his Latinity elegant, and he continued writing treatises in Latin well after this ceased to be the fashion; Pliny was also one of the most cited authors in his works.

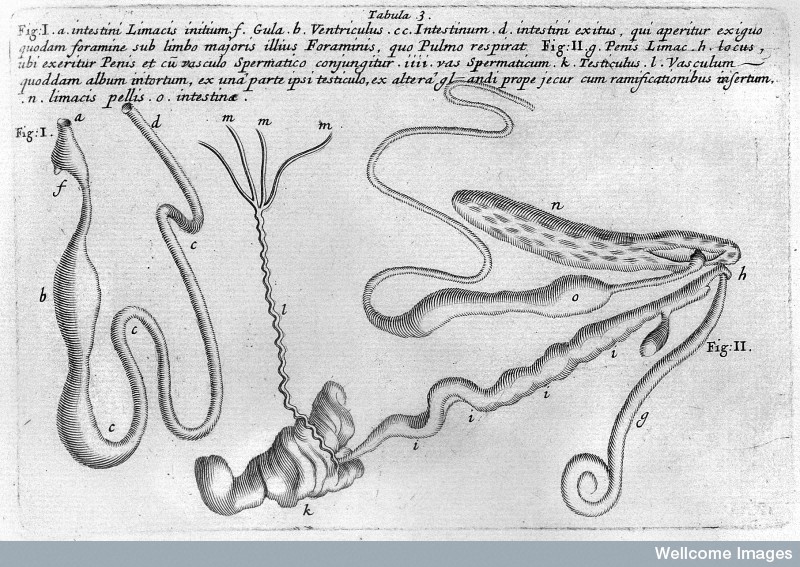

Lister stretched the Plinian idea of ‘historia’ to its limits, writing medical case histories, antiquarian histories, and the natural history of insects or ‘small animals’ including molluscs, considering them of equal importance to all other types of histories. He then refined these histories, in accordance with a new emphasis on rational empiricism, by making his own keen observations.

Lister stretched the Plinian idea of ‘historia’ to its limits, writing medical case histories, antiquarian histories, and the natural history of insects or ‘small animals’ including molluscs, considering them of equal importance to all other types of histories. He then refined these histories, in accordance with a new emphasis on rational empiricism, by making his own keen observations.

- Giovanna Pomata, Historia: Empricism and Erudition in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge, 2005), 109 ↩