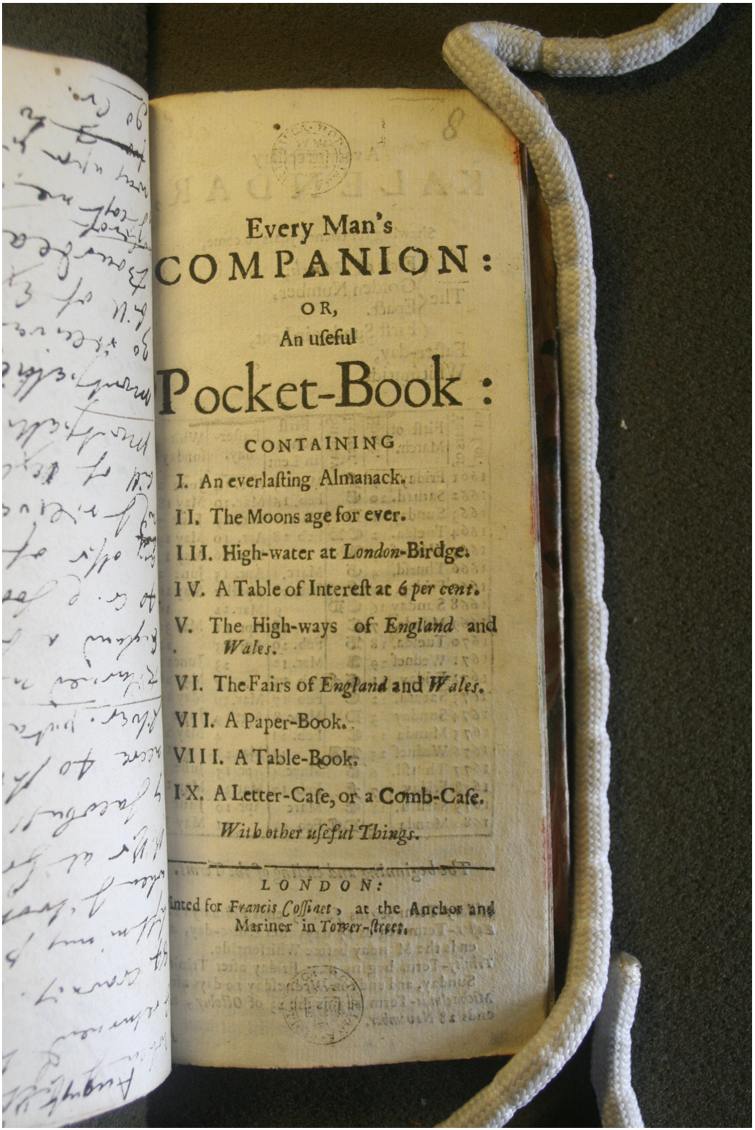

Every Man’s Companion is a bound pocket book of seven octavo paper quires, the second quire being printed. The volume has a mid-brown tanned sheep leather inboard binding. At the fore-edge it is only turned-in over the outer board layer thus forming a pocket between the two boards, the ‘letter-case, or a comb case’. 1.

Every Man’s Companion is a bound pocket book of seven octavo paper quires, the second quire being printed. The volume has a mid-brown tanned sheep leather inboard binding. At the fore-edge it is only turned-in over the outer board layer thus forming a pocket between the two boards, the ‘letter-case, or a comb case’. 1.

When first bound the volume would have comprised 56 leaves; 8 printed and 48 blank. The book now has 50 foliated leaves and torn stubs for the missing leaves, one printed and five blank. All the blank leaves are a fairly heavy writing paper (approx 0.152-0.178 mm. thick) and the printed leaves are a thinner paper (approx. 0.102-0.139 mm.). The stubs from the missing blank leaves show that they are the same paper stock and were not prepared table-book leaves, whose erasable surface was made from a mixture of gesso and glue, allowing one to write on it with soft metal, graphite or ink. 2

Although there were no prepared table-book leaves, the editor of the almanac did explain how to erase one’s mistakes: Having a black-Lead-Pencil, write therewith upon fine white Paper (as with Ink) what you please; and when you would take it off again, (as from a Table-Book) take a piece of new bread, and rub upon the writing, and it will take it clean off, so that you may write any thing there again. Perhaps to some this may seem idle and ridiculous: but it may easily be experimented, to satisfaction. Keep a Black-Lead-Pencil in your Book, and it will always be ready for Memorandums.

Graphite pencils would still be relatively new in the seventeenth century and another form of erasable writing. As neither the pencil nor the tables were provided, Lister had to make do with a blotchy quill pen.

The earliest example of an erasable table book dated from Antwerp in 1527, and they were mass-produced in London by the end of the sixteenth century. Table books even featured in Shakespeare. Hamlet when having seen his father’s ghost: ‘Remember thee? Yes, from the Table of my Memory, Ile wipe away all triviall fond Records‘. ‘Hamlet imagines his memory as an erasable table book that can be wiped clean,’ a Lockean tabula rasa. 3

For Martin Lister, the pocketbook served a much different purpose, as a memoir of his experiences, a list of the books that he read—his Lectiones Achévees—whilst in Montpellier and a small commonplace book to record details of botany, zoology, and the descriptions of crafts and techniques to ‘put Nature to various uses’. His dedication to note-taking was typical of early modern physicians and natural historians. Due to the vast and varied nature of particular observations that characterised the realm of physic and natural history ‘lost notes meant lost information’. 4

- The physical description of the almanac was kindly provided by Andrew Honey, Paper Conservator, Bodleian Library, University of Oxford ↩

- Peter Stallybrass, ‘Printed Collections and Erasable Writing’, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 150, 4 (December 2006), 553-567, on 559. ↩

- Stallybrass, ‘Printed Corrections’, 559. ↩

- Richard Yeo,’Between memory and paperbooks: Baconianism and natural history in seventeenth-century England’, History of Science 45 (March 2007), 1-46, on 8. ↩