France (Wikipedia)

Mentions in Memoirs: Folio 215, Folio 217, Folio 221, Folio 224,

Mentions in Pocketbook: Money Matters, My Correspondence, 16 January 1664, 18 January 1664, 30 March 1664, 26 August 1664,

Lister’s experiences in Montpellier were crucial to many aspects of his professional development. He traveled to Montpellier during the most convenient years for most gentlemen to travel abroad, between leaving university and settling down to married life. 1 Not only was he going on his peregrinatio medica to earn professional credentials, but also to attain accomplishments becoming of a gentleman of quality, a cosmopolitanism to add polish to his English education. Sir Thomas Browne wrote to his son in 1661, advising him to lose his pudor rusticus abroad by practicing a ‘handsome gard and Civil boldness which he that learneth not in France travaileth in vain’. 2

Montpellier was a popular choice for English medical students, not only affording the chance to learn the French language and politesse, but also possessing a fine university and renowned academies for foreign students in a beautiful setting with over 300 days of sunshine a year. Montpellier’s reputation rested to some degree on its facilities, especially its Jardin des Plantes, donated by Henry IV in 1593 and first directed by Pierre Richer de Belleval, the chair holder in anatomy and botany from 1593-1632. The oldest in France, these gardens would eventually be reorganized by the great botanist Pierre Magnol (1683-1715), who had received his M.D. shortly before Lister’s arrival. Magnol was the first to publish the concept of plant families as we know them, and the garden was separated into plants’ known eighteen medical and ‘therapeutic duties’. 3

Clearly at Montpellier, medical professors were ‘eager to show students examples of the simples used in their medicines, a knowledge that doctors had previously be expected to learn on their own’. 4

Montpellier was also known for the diverse arrangements established in the town for clinical, pharmacological and anatomical instruction. When visiting Montpellier in the 1660s, John Ray noted the ‘number of Apothecaries in this little City is scare credible, there being 130 shops, and yet all find something to do’. 5 Many offered private lessons to aspiring medics. Indeed, as typical to medical students at the time, Lister’s correspondence reveals he lodged with an apothecary, one Monsieur Fargeon, to learn by informal instruction the names and preparations of particular drugs. Lister also went on simpling expeditions to see the plants in vivo.

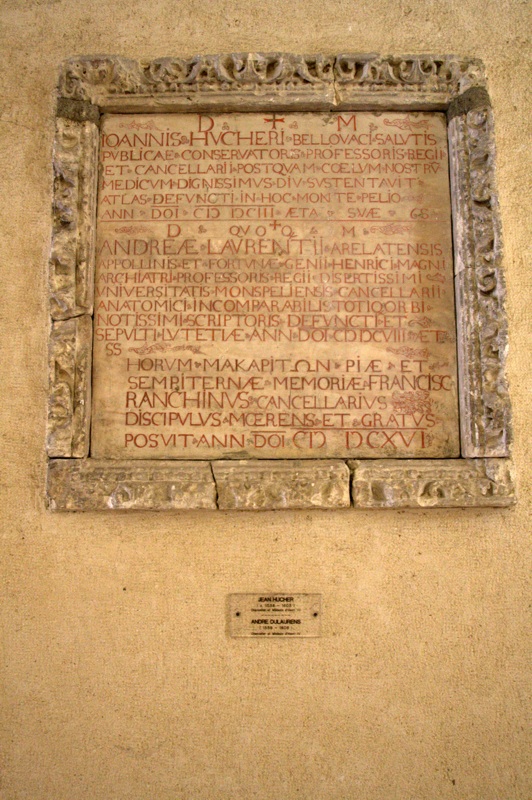

In the early sixteenth century Montpellier attracted large numbers of students from abroad, foreigners comprising 37% of the student population. 6 Although student numbers severely declined during the Wars of Religion, the Wars and their outcome ironically ‘proved to be the making of the town in respect of medicine’. Montpellier was a Huguenot stronghold, and the ‘faculty was subsequently closely identified with Henri IV and the Huguenot coterie . . . during the king’s ascendancy chairs devoted to anatomy, botany, surgery, pharmacy in addition to the four regents professorships that had been founded in the late fifteenth century’. 7

The four Regius Professors, and the year-long course, were by the seventeenth century considered at that time to be the best for preliminary medical studies. When the professors paraded once a year in their scarlet satin robes and ermine hoods, it was a matter of splendid ceremony and civic pride; in the seventeenth century ‘without doubt Montpellier hosted the most international medical faculty in France’. 8

After the town capitulated to a royalist army in 1622, the religious violence that occurred between 1560 and 1622 also did not generally reoccur; the crown and Catholic church made significant efforts to ensure the loyalty of the population, building a citadel garrisoned by royal troops. A series of reforming bishops instituted a program of conversions, and invited reforming regular orders to establish houses in the city, and by 1656, the Capuchins, Dominicans, Carmelites, Jesuits and Fathers of the Mission were established in Montpellier. There did continue to be a Protestant community in the city, but its power was severely diminished by 1650. 9

Scholar Gillian Lewis paints an even grimmer picture for Protestants in Montpellier, particularly foreign ones:

Seventeenth-century English gentlemen, attracted to Montpellier by its reputation, may have been surprised to find how few and how peripheral Protestant scholars were in the university, and how uncertain was the security enjoyed by Huguenots under the increasingly fragile Edict of Nantes. As foreigners and Protestants, they were barred from formal matriculation in the University of Medicine and were therefore forbidden to attend its lectures or disputations. The only exceptions were the occasional official anatomy, more a public spectacle than a serious investigation, and the demonstrations of the official herbarist in the botanical garden, which non-members of the university could also watch at a distance. 10

This may have well been why Lister trained with Monsieur Fargeon and accompanied Ray on so many simpling expeditions. Our videos below shows the type of landscape he would have encountered in Languedoc, with close-up views of wild tansy, long employed for a variety of medical uses.

- Sara Warneke, Images of the educational traveller in early modern England (Leiden, 1995), 79. ↩

- Geoffrey Keynes, ed., The Works of Thomas Browne (London: Faber and Faber, 1964), vol. 4, pp. 4-5, as quoted in Warneke, Images, 49. ↩

- Pierre Magnol, Hortus Regius Monspeliensis (Montpellier: Honoratum Peck, 1697); L. Bertrand, Granel de Solignac, ‘Les herbiers de l’Institut de botanique de Montpellier’, Naturalia Monspeliensia, série botanique, 18 (1967), 271-292. ↩

- Harold Cook, ‘Physicians and Natural History’, in Cultures of Natural History, eds. Nicholas Jardine, James Secord, and Emma Spary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 91-105, on 96. ↩

- John Ray, Observations Topographical, Moral and Physiological; Made in a Journey Through part of the Low Countries, Germany, Italy, and France (London: John Martyn, 1673), 454. ↩

- Elizabeth Williams, ‘Medical Education in Eighteenth-Century Montpellier’, in Centres of Medical Excellence? Medical Travel and Education in Europe, 1500-1789, ed. Ole Peter Grell, Andrew Cunningham (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2010), 249-50. ↩

- Williams, ‘Medical Education’, 249-250. ↩

- Hilde de Ridder-Symoens, ‘The mobility of medical students from the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries: the Institutional Context’, Centres of Medical Excellence, 64. ↩

- See Tim McHugh, Hospital Politics in Seventeenth Century France: The Crown, Urban Elites and the Poor (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), 112. ↩

- Gillian Lewis, ‘The debt of John Ray and Martin Lister to Guillaume Rondelet of Montpellier’, Notes and Records of the Royal Society 66, 4 (December 2012), 324-325. ↩