Apothecary

Mentions in Pocketbook: January 1664

Montpellier was known for the diverse arrangements established in the town for clinical, pharmacological and anatomical instruction. When visiting Montpellier in the 1660s, John Ray noted, to his great surprise, that there were 30 apothecaries shops within the town walls that ‘all find something to do’. Many offered private lessons to aspiring medics. Indeed, as typical to medical students at the time, Lister’s pocketbook reveals he lodged with an apothecary, one Monsieur Jean Fargeon, to learn by informal instruction the names and preparations of particular drugs.

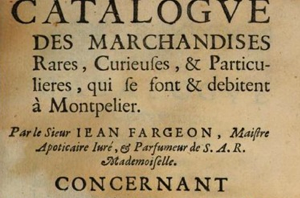

Lister could thus see the plant in vivo in the Jardin des plantes in the medical school, and in vitro in the apothecary’s shop of Monsieur Fargeon. Fargeon’s original sales catalogue from 1665 may be found here, so we may get a sense of what compounds Lister was learning to make.

This hands-on approach was typical of education there. As Montpellier was unusual in having ‘no arts faculty to serve its propedeutic needs’, as Ian Maclean has stated, there was a long tradition there of ‘practical medicine which did not lay great stress on the Aristotelian logic behind medical precepts’. This would be in direct contrast, for example, with Italy where the prominent role of ‘logic in the arts faculties may have predisposed professors in the medical faculty to seek more actively for an accommodation of their discipline with Aristotle’s Organon’ 1.

Fargeon’s Published Catalogue

As for Jean Fargeon, he was an apothecary and performer of royal privilege, or Apoticaire Iuré et Parfumeur ordinaire de S.A.R. Mademoiselle d’Orléans. The Fargeons’ shop was in central Montpellier, vis-à-vis the Cheval Blanc on the Grand Rue (now the Grand Rue Jean Moulin), across from the Traverse des Grenadiers. The shop was called Le Vase d’Or or the Golden Vase. As Elizabeth de Feydeau stated, by 1668, Fargeon “had perfected the recipes of a large number of products, classed according to usage as either ‘compositions for health’ or ‘perfumes for embellishment’”. 2.

The Fargeons would by the eighteenth century reorient their family business; Fargeon’s descendant Jean-Louis would become the official perfumer for Marie Antoinette. You can still buy adaptations of Jean-Louis’ original perfumes, and the Fargeons’ firm is still extant, now known as GELLÉ Frères. If you click the link, you can see one of Jean Fargeon’s early advertisements. It is also possible to see lists of some of the products that the Fargeons made in this article about inventories of early modern French apothecaries.

Lister sent his younger sister Jane some books and some French perfume, and she told him in a letter:

[M]any thanks for your parfums they are most rarely good, I am confident the parfum that Madam de Bourdet sent Balzac ware not so good although he could commend them in better words then I can doe yet he could not esteem them more.

Letter, ca. 1663-1666

Jane referred to one of Lister’s favorite (or at least most mentioned) authors in his student notebook, Jean-Louis Guez de Balzac (1597–1654). Balzac was a member of the Académie française. Balzac’s published correspondence introduced new stylistic qualities of precision and clarity to French prose. Balzac said of the perfumes he was sent, ‘I speake not of the delicacy of your perfumes, in which you laid mee to sleepe all night; to the end, that sending up sweet vapours into my braine, I might have in my imagination, none but pleasing visions’. 3.

Jane was paying her brother a high compliment indeed for his gifts. Perhaps Fargeon made the fragrance for his young lodger to send to his sister.

Back to top

- Ian Maclean, Logic, Signs, and Nature in the Renaissance: The Case of Learned Medicine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 30 ↩

- Elizabeth de Feydeau, A Scented Palace: The Secret History of Marie Antoinette’s Perfumer (New York: I.B. Taurus, 2006), 9 ↩

- Jean-Louis Guez de Balzac, Letters of Mounsieur de Balzac. 1. 2. 3. and 4th Parts. Translated out of French into English. by Sr Richard Baker Knight, and Others (London, 1654), 389 ↩